THE VISUAL NATURE OF

STORIES AND STORYTELLERS

PREFACE

Visual storytelling is as

old as the time curious, human creatures have walked about the earth searching

for something beyond their grasp. It is as much an imprint of the timeless

human spirit’s need to create as any fossil found.

Throughout history samples

of human, storytelling artifacts have defined the past. We know more about who

we are because we know something about the stories that tell us from where we

have come. Whether it be the drawings on the cave walls of Lascaux, stone

reliefs hieroglyphics from ancient Egypt or Mickey Mouse dancing and singing on

the screen, they all represent the humans need to convey story through imagery.

Unfortunately, the past can only be defined by too few creations that have

survived the harshness of time, never to see most of the imagery human

designers have created over the ancient past. Even today there are many classic

motion picture films that have not even survived a century. By the next century

someone will hold a DVD and claim it represents a story of the past but they

not how to decipher its meaning.

The human animal has a need

to relate to the stories rumbling in their brain because the very essence of

the human experience exists within groups and individual clusters of story

packages. Long before letters formed words, and words told stories, the human

animal tried to understand the visual world around it, real and imaginative,

and translated that imagery into early visual dictionaries within the primitive

mind. Somewhere, around an ancient fire, some storyteller, through various

grunts, hand gestures and natural props, told stories communicating noble

victories and cruel defeats; stories that inspired and haunted those ancient

audiences, but stories that lived in each of their minds for life and retold

throughout countless generations; to nourished the cravings that only stories

could satisfied.

The human animal is a

visual animal in every way. They have survived with the assistance of their

keen visual discrimination and their ability to communicate through imagery.

They translate visually the real as well as the metaphysical universe which

they sense around them. They use images and stories in an attempt to organize

chaos and rationalize the irrational.

They have abilities to

record visual memory and create new visualizations in the abstract form which

then can create a new reality.

A gatherer/hunter learns

from past events; when the sun is warm there will be yellow berries by the

river… or, every time they rush the animal from one direction the animals runs

away in the opposite! So, this time we should try something different- half the

hunters walk in front while the others will go around the big rock and come up

from behind-we will catch the animal by surprise... surround it…and we will

have all food tonight!

Such ability to

pre-visualize strategies and tactics, in another place and time, are the

storytelling nature of the human animal.

Today we have the

technology and artistic skills to create masterful visual representations, but

to what end other than to simple satisfy the human need for story.

Everything about how we

humans think, dream and translate the world around us is through some type of

visual storytelling. And yet, how much emphasis is placed on the awareness and

education of this vast visual language?

In this study of Visual

Language, we will draw on this natural, human tendency and discuss how

designers of visual storytelling can learn to create more effective stories,

and thus more effective communication

THE STORY ARC: HOW CAN

SOMETHING SO SIMPLE HAVE SO MUCH POWER?

There are some who diagram

stories like elaborate flowcharts. It is one of those things that seem to make

sense in theory but somehow fizzle out in application. I have even seen a

concept for story visualized like some kind of unfathomable mathematical

formula- to each their own I guess.

To me, the simplicity of

the Story Arc is as good a model to play any story against. It reminds the

storyteller of what’s important without being too intrusive in hindering the

creative dynamics you seek in telling each tale.

Stories basically are

caricatures of life. Most every film, book, or song is somehow rooted in human

reality and exaggerated by symbolic or metaphorical means. Someone once said

‘Films are all about real life seen through a distorted lens with all of the

boring stuff cut out onto the editing floor.’ The same can be said for any

story told regardless of the venue.

In a way, a storyteller is

a chef; good stories are ones that relate to the personal appetites of the

audience. The author’s genius lies in their ability to simplify and exaggerate

each detail so that it tastes great and is good for you-during and after the

experience.

It all comes down to the

fact that humans have a need for stories, and relate to them so well because

stories exist within the same fabric of how they perceive, and interact with

real life. There is a basic need for stories, whether they simplify the

complex, offer escapism from harsh reality, or reinforce the meaning within

dreams and desires.

THE STORY ARC

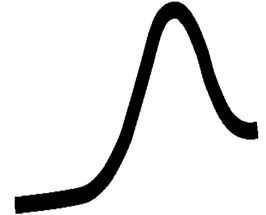

When you first look at the

image above of the Story Arc it first brings to mind the notion of every

storyteller’s most important tool-Observation. Most people see a wavy line,

nothing more. But this line has important characteristics that can guide the

most complex story intricacies.

I could spend hours talking

about this simple curved line. To state that this small image holds the guide

to every mystery of storytelling would suggest that I might be prone to gross

exaggerations- which is probably true, but I won’t say it. Within its simple

design lies a very useful tool, which is to guide the execution of any story.

So, let’s begin to breakdown this diagram as to its meaning and help tune your

perceptions to see relationships between it and the stories you wish to tell.

The first thing noticed

about the Story Arc is that it is not symmetrical. Unlike an audio sine wave

which has a base value, rises to reach its highest point, and then returns back

down to the same base over a specified rate of time, the Story Arc does not.

The Arc basically spends

about two-thirds of its time rising to its highest point, and then downward the

remaining third. If it is a three hour film, which translates into a two

hour-one hour ratio; for a thirty second commercial, and twenty -ten second

commercials; all approximately speaking, of course.

Also to note is that the

Arc starts lower and ends higher.

It probably does not need

to be mentioned, but I will anyway, that these two, all important

characteristics of the Arc are relative. That is to say that the design and

proportions stated above are from a figurative point of view, not a literal

one. It is meant only as a guide to use as a loose template to explain broader

issues about story development. No story I know is so mundane that it would fit

exactly within this design.

STOP PLAYING WITH OUR

BRAINS

A good story has a

Beginning-Middle and End. Duh!?!

To continually use the

Story Arc design as a model to describe more specific topics, it is important

to divide the entire arc into three sections. These represent the three

sections of a story: the long upward slope of the Arc is the Beginning or

Introduction of the story elements; the top of the Arc is the Middle or

Conflict; and the downward slope is the Resolution or the End. To go back to

our food analogy, a story is like a three-course meal.

Now, when I introduced this

section to my students, I prefaced it with a statement:

Today we will be talking

about story development. To start, there are three parts to every story, which

as storytellers, you should be well aware.

This information will be on the final exam. I

suggest you write this down. I will wait until everybody is ready…are you

ready? ...the important three parts to any story are; The Beginning, The

Middle, and The End.

I would usually get a

chuckle from my brightest students. Another group seriously wrote it down and

then looked up a bit perplexed, and then there were some…well, I am not exactly

sure where they were on this.

I really wasn’t trying to

be funny, only ironic. You know the difference don’t you? I did however keep my

word-that question was on the final exam. Did everyone get it right? I’d rather

not say. You who are teachers might understand.

The fact is, if I could

only teach students one thing about story development, it would be learning

these simple three things. I explain the reason to emphasize this seemingly

oversimplified point-because simply good stories have it and poor stories do not.

To relate the point, I clarify my emphasis by pointing out that I noticed most

of the stories students submit to me for critique lack some, or all, of these

three simple guidelines. There is no better way to create humility in students

(an important step to begin learning anything new) than to point out the basic

flaw in the foundations of their own work!

My example might flow

something like this:

I am reading a student’s

story, trying to get oriented to what they want to say; the meanings of the

events are unclear; the relationships of their characters are unfulfilled. I

have no idea who the characters are, or why they are in their story, so what

they are doing has little relevance; there are no proper introductions to the

characters-I don’t know them, or don’t want to know them. And, the setting,

theme, conflict, etc. of how the story unfolds has little meaning.

Or, they have a bunch of

action going on suggesting conflicts, but I don’t know the rules. What is your

story-logic? There is no real identity for each story element, no set-up for

resolution, no ending, no clear reason to be! Like me, the audience is left

wondering what it’s all about. For all we know those conflicts might still be

unresolved today!

Then… there are those

stories that tell me only all about a character, thinly disguised as the

profile of the student-author, who I get to know more than is comfortable. But

the story doesn’t go anywhere because their own personal story is mostly

defined-still unresolved! The story is told as if the character was sitting in

front of the mirror talking to themselves. Perhaps this character study is some

sort of cleansing, psychological therapy for the author, but of little

relevance to your unknowing, uncaring audience.

Ouch! Well, a good lesson.

If nothing else, the audience should always care. After all, a story you create

is for them, not you, the author; a good lesson to always remember!

Students who create these

clumsy stories often lack an understanding of how to visualize a story within

the template of a Beginning, Middle, and End. Once they get this model in their

heads they begin creating a higher plane of storytelling-one in which audiences

can begin to engage. It is how the audience measures the events that unfold

within any story. It is how they can relate to each detail; it becomes their

story.

Audiences want a lot; but

they want at least a Beginning, Middle, and End.

The human animal interprets

everything of the world around them in terms of stories. In that natural

processing, humans sort through all this in terms of; who are the players,

what is the situation; what is happening, and what does it all mean.

Even though the storyteller

might not do their job to satisfy these queries, the audience seeks them out

nevertheless-though often in vain.

With this perspective

prefaced, let’s look at those three parts that we divide the Story Arc into;

Beginning, Middle and End, or Introduction, Conflict and Resolution.

INTRODUCTION, CONFLICT AND

RESOLUTION

Humans see life, think

about life and live life within the context of a simplified and exaggerated

story structured with interactions. Though most great stories are wonderful,

fantastic, and inspirational escapes, there is always a relationship back to

one’s own life. If stories are nourishment to the imaginative soul, that soul

still exists within the body of a human, who exists in their reality of a

life-such a body needs to be nourished with stories.

Humans have a natural

tendency to define Good and Evil. They comprehend the notion of life as a

journey. They have a natural curiosity to become acquainted with other

characters, both human and animal, which they define as personalities; good and

evil. Together they evolve toward closer relationships, or further apart, as

more traits are revealed-traits defined as either appealing or repulsive.

Humans seek love and friendship, and learn the pains of loss. They are aware of

life’s ironies, agonize at their shortcomings, yet, relish each triumph, both

large and small.

Each human has their own

ideas about faith, trust and a rationale of comprehending those things that

defy explanation. They have their own take concerning goodness, justice, and

eternal damnation. They are part of the collective body of other human animals,

yet pride themselves in their stubborn uniqueness.

Every animal needs to love

and be loved. They crave excitement, thrill and seek every opportunity to

laugh. They understand irony, metaphors, and allegories, if presented properly.

It is all the stuff that

great stories are made of. So, if the parallels between real life and

entertaining stories are so close, then why do we need stories?

Simply put, we are human

animals, and in order to survive we need story nourishment; physically,

mentally and emotionally. Real life does not fulfill all of these basic needs.

Only story-interplay can balance the natural human-animal appetite for such needs.

Also, stories serve another

very useful need in helping us better define those things that we don’t

understand, invisible things we ponder. Such virtual story exercises help us to

rehearse and pre-visualize future events in order to become familiar with

issues and help define how we feel about things that haven’t happened yet, or

may never occur.

With that esoteric

digression out of the way, let’s get back and discuss story structure.

The other thing you may

have noticed about the design of the exampled Story Arc, is that the level in

which it ends is higher than where it started. This implies that for every

story told we must be taken on a journey from which we begin at one plane and

end at a much higher plane.

If it is the goal of the

recipient for any story to be transformed by the interaction, then it only

makes sense that we should end somewhere else other than from whence we

started; preferably better or at least enlightened by the journey. Even a

thirty second commercial aims so high:

Character is miserable, if

he uses product X his life will change. Bam, he has been transformed and his

dreams are fulfilled.

You think I am being

ironic, but analyze ten commercials and draw your own conclusions.

As the introduction of

characters, setting and plot begin to unfold in the Introduction part of the

Arc, it is worth mentioning a very powerful dynamic used throughout the story

process, the concept of Contrast.

Part of the exaggeration

process of every storyteller is the notion that everything becomes polarized

for the sake of clarity. Remember, the two greatest tools of any storyteller is

simplification and exaggeration.